Tips and tricks: Scientific Papers

|

Writing articles is a core task in doing a PhD: enjoyable for some, but a hellish experience for others. Find below tips and tricks useful to streamline the process. |

|

PlanningNext, a realistic planning is required. Be advised: in many fields, gathering the data for the paper is only a minor task. Making the figures and writing the article are considered a substantially more hefty task, involving dedicated intellectual input. Getting data is one thing, interpreting them well, and placing them carefully in the right scope within the existing literature is quite another...

|

Figures FirstOne thing that is recommend in the planning is to prepare (publication-ready) figures first. This exercise will make you also intimately familiar with your data, something which concomittantly facilitates further writing. Tips and tricks on making scientific figures can be found below.

|

Learning along the wayDuring the writing you may learn that certain hypotheses/interpretations you held at the beginning of the process are no longer correct. This is nothing bad: in fact these represent valuable lessons that make your paper stronger. Make sure to communicate these results clearly to your coworkers and act accordingly. For example, it may be desirable to perform extra experiments to strenghten your paper.

|

Self-criticismBe advised that as the first author you hold the core responsibility for what is written down and what is published. Do not write for your supervisor, do not write to please referees/editors, instead write to make a high-quality publication from your results. In whatever you do: be self-critical. Double check things. Do not forget: published is published. Referees are not going to stop you from making a fool of yourself!

|

|

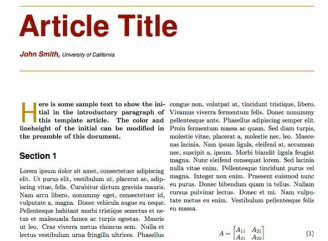

Journal (template)With the key data identified, it useful to choose a good journal. Each journal publishes different types of articles and it is worth the effort to check which one suits your data best. In addition, most journals provide online instructions as well as templates from which your can work. Choosing the proper journal is a delicate task requiring some experience. So ask your superisor(s) for feedback. After you submit to a journal, it often takes several weeks before you hear something. Therefore, choosing the right journal from the start may save you loads of time...

|

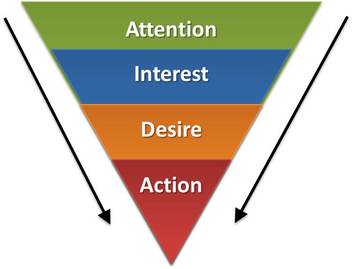

Introduction: general to specificAlright, you got your figures and your skeleton made in the right journal template: time to start writing! A part that can be started early in the process is the introduction. It is important that the introduction is used to briefly introduce the topic to the reader. Accordingly, it should go from a broad attention to the topic, to an interesting/promising part of that topic, to things that are desired/problematic in this particular field, to the super awesome stuff you have done that solve all these issues. Mind you; not everything needs to be explained. This is not a tutorial review. For common articles, keep it to ca. 1000 words or less. Usually: the more impact your work has: the smaller the introduction!

|

Introduction: the 'herein' paragraph This last paragraph describes what you actually present in your work and should be sexy. It should seduce the reader to keep on going. Accordingly, it may be preferred to not simply and unambigiously diclose all your results, but to say what you did in a bit of a carsalesman's kinda way: "how certain overlooked aspects help to overcome existing limitations, achieving unforeseen performance by utilising the interplay between xxx and xxx." It should be a bit like the label of Nutella jar: you get all excited to put some on your knife! Do you get my draft?

|

Experimental: Been thereThe experimental part is often the easiest. Simply write done what you did and how did it. Ask yourself the question: "would people be able to reproduce exactly what I did? if the answer is no: specify further. If you used techniques that you have used before: simply see how you wrote it down before. There is no need to reinvent the wheel ;)

|

Experimental: sample codingSample coding that is easily interpreted will make everybody happy! So do yourself and all others a favor and think about this just a bit longer! As mentioned above, people hardly ever read your paper in full detail, so having a intuitive sample coding will ensure your paper gets the attention it deserves!

|

'3. Results and discussion'

|

Present versus past tenseDuring my studies, a strict use of past and present tense was imposed. However, in publications these rules are surpisingly rarely enforced. In general, try to write the abstract in the present tense. In addition, try to write general truth in the present form, and the experiments you performed in the past tense. An example: "Elemental analysis of Nutella revealed that the sugar content was 58 wt.%. This implies that Nutella is of similar sweetness compared to other commercial chocolate pastes"

|

Word inflationIt is recommended to be economic with words. If you are self-critical enough, you may be able to recognize some rather 'useless' words in your writing. For example: "In fact, it seems that". These 5 words do not add anything and are best left out. The work by R. Day (see link above) contains a nice list of examples.

|

Overcautious writingEspecially new students often write too carefully. For example, if a certain figure shows an increasing trend, it should not be described as 'seems to be increasing' but with 'is increasing'. If something is obviously clear, then write it like this. Only when you are speculating on possible implications you should apply caution with words as 'may, might, should'.

|

|

Figure and Table referencesWhen to refer to a figure or table? This is a tough one to answer in a universally-applicable fashion, especially if the data if repeatedly referred too. Refer to them the first time you mention the relevant data. Try to limit the amount of referring to a certain figure to 1 per paragraph. If it is hard to avoid repetitive refering to the same figure, you can make a little general introduction of where the figures can be found. An example of this approach can be observed in the start of the R&D of the paper on the left.

| ||||

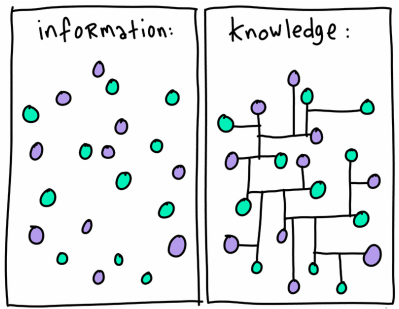

Information versus techniqueIn structuring your discussion. Try to focus on the information you have gathered instead of on the technique used. For example, instead of dedicating a section on nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), you can focus it on coordination. After all, we do not want to do NMR, we want to learn about the coordination of a certain element within the sample (using NMR). This is clearly demonstrated in the above Example paper.

|

FocusMulti-tasking, consisting out of doing many things at the same time, usually leads to a lower quality. Try to do things one at a time, and do them properly. You can easily spent a few days making a great abstract: it will be worth the effort if the quality is top. Simply light a candle, play some Marvin Gaye, and write that sexy abstract!

|

Flow: Sentence to sentenceYes: every sentence in a paper should flow into the next. That means that every part of your paper deserves your glorious and dedicated attention. It is very common that especially parts in the end are poorly written simply due to a lack of love! An useful trick is to, instead of reading your manuscript from the first part (abstract), start reading from the back...

|

Say it as it isDuring writing you may sometimes find it hard to describe things accurately. In such a case, it may be good to take a step back, take a deep breath and to try to think of what's going on (Marving Gaye reference). Then, when you are ready, 'say it as it is' using initially simpel words. Afterwards, when you are happy with your argumentation, you substitute those simple words for more accurate ones. Another valuable tool is to shorten sentences to tackle the topic part by part.

|

Break the dogmaOften, especially as a novice Ph.D. student, you will run into things that everybody says or does, but that simply do not make sense. In such a case, instead of covering it up and avoiding the issue, name it, try to get advice from your supervisors, and -if possible- solve it. This may require extra experiments, but will strenghten your paper. You may even plan carefully and use the experiments for a second 'spin off' paper!

|

7 C's: Complete, Concise, ClearScientific sentences should be complete, concise, and clear. An approach to achieve this is to remove any possible ambiguity from the sentence. Ask yourself the question: 'can the sentence be interpreted in any non-intended way?' If the answer is yes, try to refine your sentence.

|

7 C's: Consistent, Correct, Considerate, ConvincingThe remaining C's: These will help to enforce the above 3 C's, and need little further elaboration. Within the academic circle it is important to write also considerately: Eventhough you may not agree with other works, you should always describe other work in a fair and objective manner. In trying to be as convincing as possible, you could use examples.

|

The broad picture: dare to generalizeAfter you have finished your R&D, you may have gathered a unique perspective on the matter. Well done, that's the purpose of being a scientist! Ideally, you could use this perspective to generalize or review the existing works on the topic in your paper. To do this in the strongest possible fashion, you could compare your data with those from the existing literature. Generalizing can be nicely done using conceptional graphs. The good thing of such graphs is that they are extremely insightful but do not require extra experiments to make. Moreover, these figures will make your work more cited! Of course, be careful in your generalizations, and add disclaimers if needed.

|

Supporting informationIf you find yourself in a surplus of figures, you may put some in the supporting information. Particularly those that are derived from routine analysis and bring no added value may be easily be placed there. Sadly, the supporting information is also often used to 'hide' unfavourable results...

|

Acknowledgments and fundingMention those that contributed but not enough to justify being an author. Funding should be always acknowledged. The latter may seem unnecessary, but do not forget that the people in charge of giving the grants (including the one you may be enjoying right now) are also keeping track!

|

ReferencesThe references should be done in the style of the journal. Although software can be used to facilitate this (such as Endnote), they often imply difficulties further down the process. Accordingly, especially if you have ca. 60 or less references: you could try to do it by hand! Old School those babies!

|

Graphical abstract The graphical abstract should cover the most basic message of the paper. It is often depicted rather small. Therefore, try to keep it simple. People have little time to study it and it should bring your message across within several seconds. PowerPoint can be suitably used to make graphical abstracts (see tips in the Arts section). Bonus tip: if you are lacking inspiration: ask your colleagues and even friends for help or inspiration!

|

Abstract vs herein vs conclusionsIt can seem confusing to distinguish the abstract, the herein paragraph of the introduction, and the conclusions. An visual aid to highlight the differences may come in the form of the nutella jar: the abstract is formed by the dry nutrition facts. The tasty-looking label is the herein paragraph. Then, the conclusions, showing the implications of a tasty chocolate paste, is a content and happy child eating Nutella. (Finally, in the supporting information you can mention that exposing your kids to a high sugar diet might be bad for their health).

|

Bonus: patent literatureOne thing that remains (sadly) often completely overlooked is the patent literature. This is surprising as these works reflect the 'real' world probably more accurate than scientific papers. If you really want to make a dent, make sure to also check patent literature. Particularly the background of the inventions may enlighten you!

|

Further reading:In addition to the above-mentioned, epic contributions by the esteemed Dr. F. Mumpton and

Dr. R. Day may further enlighten you (see links below). They may be old, but they are still extremely insightful.

Update I: check out the author instructions from Dr. Chiara Farinelli, Publisher Statistics and Mathematics. A very useful contribution indeed!

Update II: another interesting work by Dr. Reuben Hudson on the similarities between scientific and dramatic writing can be found below:

Update III: nice job by Dr. Carol Potera highlighting some useful lessons on writing:

Update IV: for more tips on writing articles (and scientific communication in general) check out the work by Marta Davis:

| ||||||||||||||